Permissible Inference or Impermissible Burden Shift: How the Supreme Court Could Decide State v. Glover

by Judge Daniel M. Coble | March 18, 2019

In Unreasonable Suspicion: Kansas’s Adoption of the Owner-as-Driver Rule, Benjamin Donovan gives a spot-on analysis of the Kansas Court of Appeal’s ruling in State v. Glover. Donovan makes an articulate and convincing examination of the issue he sees most glaring in this case: reasonable suspicion (or the lack thereof). However, I believe that this case hinges on something more important: burden shifting. And if the Supreme Court is to grant the state’s petition for certiorari, it will do so to address this fundamental issue.

State v. Glover

The facts of the case are straightforward and were actually stipulated to at trial. A sheriff’s deputy was on patrol when he ran the license plate of a vehicle driving on a public roadway. The information came back that the registered owner’s license was suspended. The deputy initiated a traffic stop, not for any traffic violations, but based on the assumption that the registered owner was driving the vehicle while his license was suspended. The district court tossed the case based on a lack of reasonable suspicion to initiate the traffic stop, holding that “it was not reasonable for an officer to infer that the registered owner of a vehicle is also the driver of the vehicle absent any information to the contrary.”

The Kansas Court of Appeals overturned the district court and viewed the reasonable suspicion in an almost inverse view. The court stated that an officer has reasonable suspicion to initiate a traffic stop if the officer knows the registered owner has a suspended license and “the officer is unaware of any other evidence or circumstances from which an inference could be drawn that the registered owner is not the driver of the vehicle.” The Kansas Supreme Court overturned the Court of Appeals and held that the officer did not have reasonable suspicion for two reasons. First, the officer “assumed” that the registered driver was the actual driver of the vehicle without knowing anything more. Secondly, the court held that the state impermissibly shifted the burden to make the defendant prove that he was not the driver.

A Factual Argument

A cursory reading of both the petitioner and respondent’s briefs quickly illustrates the many differing opinions that state and federal courts have on Terry stops. It is clear that while the Supreme Court’s standard for reasonable suspicion is straight forward in its presentment, its application is an entirely different ballgame. Both Glover and the State of Kansas cited multiple court opinions that they believe have similar facts to theirs. This goes to one of my central points: a fact case is not likely to be taken and decided on by the Supreme Court. Because both sides stipulated to what happened, for cert to be granted, this case will have to hinge on what the Court thinks of the word “assumption” and if that has shifted the burden.

To exemplify why a facts-based argument will not interest the Supreme Court, take one case that both parties cited in their brief. In U.S. v. Cortez-Galaviz, DEA agents initiated a traffic stop on a suspected drug dealer after running his license plate and the information for the vehicle came back as “insured/not found.” Before we go any further, you can see how easy it is to make arguments for both sides. Yes, there is reasonable suspicion that a crime is being committed, i.e., a moving vehicle that is uninsured. Or on the other hand, the system did not determine if that the vehicle had no insurance, but merely did not know. Both parties use this case, emphasizing the fact that now-Justice Gorsuch wrote the Tenth Circuit’s opinion, and other similarly situated cases to explain why there is or is not a circuit split. And, it is likely that one party could be completely correct. However, I believe the real issues of these cases is not the different factual situations that can produce reasonable suspicion, but rather who has to prove it.

Assumption vs. Inference

Under Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, a warrantless search is per se unreasonable if the person had a reasonable expectation of privacy. However, there are exceptions to the requirement that the government must obtain a search warrant. One of these exceptions is a Terry stop, which allows law enforcement to stop a person or vehicle if they have reasonable suspicion that a crime has occurred or is going to occur. During a suppression hearing, the state must prove to the court that the officer had a reasonable suspicion to conduct the warrantless stop. As the Kansas Supreme Court has held on previous occasions, the “State bears the burden to demonstrate that a challenged search or seizure was lawful.”

Why would the issue of burden shifting be more important than the actual issue of whether or not there was reasonable suspicion? The answer goes back to the text of the Fourth Amendment, which requires that searches and seizures by the government be accompanied by a warrant. Exceptions to this requirement blossomed over the past two centuries. The Supreme Court has made it clear that overcoming the warrant requirement is no easy feat, and only “exceptional circumstances, may an exemption lie, and then the burden is on those seeking the exemption to show the need for it.” A slight deviation from this burden standard might seem like a hyper-technicality, but its importance is steadfast: the government must always explain why they did not go and retrieve a warrant.

So what is about this case that makes the burden shifting so prominent? The Kansas Court of Appeals in its opinion (that was ultimately overturned), adopted a standard that some other jurisdictions have begun using. This standard is described by the Kansas Supreme Court as the “owner-is-the-driver presumption” and is summed by the Indiana Supreme Court case:

State supreme courts that have addressed this issue uniformly hold that an officer has reasonable suspicion to initiate a Terry stop when (1) the officer knows that the registered owner of a vehicle has a suspended license and (2) the officer is unaware of any evidence or circumstances which indicate that the owner is not the driver of the vehicle.

I believe that the reasonable suspicion in this standard turns not on what the officer knows, but the information that he lacks. The usual method for establishing reasonable suspicion is combining what the officer saw, heard, and smelled with his or her training and experience. However, under this “unaware” standard, the officer is still using his or her training and experience, but it is based on facts that do not exist.

The Supreme Court has granted its blessing to officers drawing inferences to establish reasonable suspicion: “This process allows officers to draw on their own experience and specialized training to make inferences from and deductions about the cumulative information available to them.” The question presented in Glover is whether or not “cumulative information” includes the lack of information too.

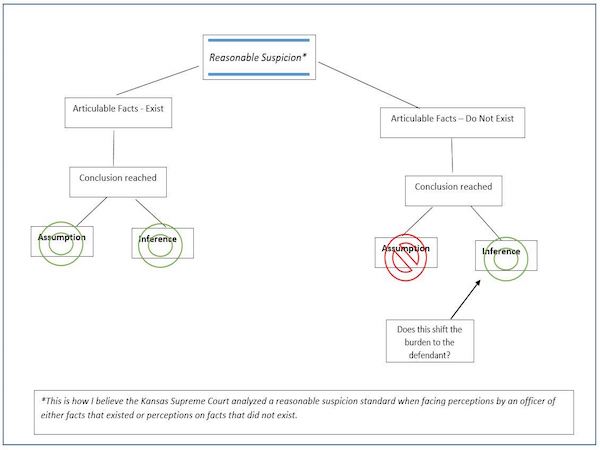

We have more than five decades of case law trying to capture the meaning and essence of reasonable suspicion and articulable facts, and there’s no reason to jump into that thicket. The real analysis is how the Kansas Supreme Court characterized the observations that the officer made. If the officer assumed that the defendant was the driver of the vehicle, then by definition that is “a statement accepted or supposed true without proof or demonstration,” which would render the search unlawful. If on the other hand, the officer inferred that the defendant was the driver, then that would be a “conclusion based on a premise,” which is permissible.

The Kansas Supreme Court’s opinion shows why the difference between an assumption and inference is so vital. The first conclusion that the officer draws is that the driver of the vehicle is likely the registered owner. The second conclusion that the officer makes is that the registered owner will still drive his vehicle if his license is suspended. The court held that both of these conclusions were assumptions, and one assumption built off of another, is simply reaching too far. But, imagine if the state was able to successfully argue to the court that the first conclusion was not an assumption at all, but was in fact an inference; that based on his training and experience, he concluded that the registered owner was the driver. While this argument might sound abstract or aloof, it is evident that the way in which the officer phrased his perceptions, assumption versus inference, clearly had an impact on this case.

View fullsize version of flowchart.

Based on this reasoning, does that mean that the Kansas Supreme Court would have sided with the officer in this case if he had actually been making an inference rather than an assumption? And, if an inference of a non-existent fact (here, that the owner of the vehicle is the driver) is legally permissible, then does a defendant then have to prove that this inference was incorrect? This is why I believe this case is so important and has the potential to make it before the Supreme Court. The Court will likely see the significance of this case, not as a split among jurisdictions about the specific issue of traffic stops based on suspended license checks, but rather see this case as an agreement by all lower courts that an inference of non-existent facts is permissible. And, if these courts believe that this type of inference is permissible, then will the Supreme Court let that stand, or has the burden shifted?

Daniel Coble is the Associate Chief Magistrate Judge for Richland County, South Carolina. He is the author of The 4th and founder of the blog Everyday Evidence. Prior to his appointment as Majistrate Judge, Daniel was an assistant solicitor in the Fifth Circuit Solicitor's Office based out of Columbia, South Carolina. Daniel is a graduate of Clemson University and the University of South Carolina School of Law.

Daniel Coble is the Associate Chief Magistrate Judge for Richland County, South Carolina. He is the author of The 4th and founder of the blog Everyday Evidence. Prior to his appointment as Majistrate Judge, Daniel was an assistant solicitor in the Fifth Circuit Solicitor's Office based out of Columbia, South Carolina. Daniel is a graduate of Clemson University and the University of South Carolina School of Law.

Short URL for this page:

http://washburnlaw.edu/coble-burdenshifting

The Washburn Law Journal Blog aims to provide timely content from a variety of viewpoints. We use an abbreviated editing process for Blog posts as compared to the traditional process used for print and online content. The views expressed on the Washburn Law Journal Blog belong to the individual authors alone and should not be construed to be those of the Washburn Law Journal, Washburn University School of Law, individual editors, other authors, or the institutions with which authors are affiliated.