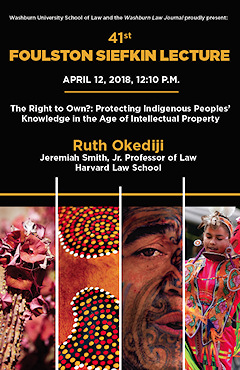

Prof. Ruth Okediji of Harvard Law delivers 41st Foulston Siefkin Lecture

On April 12, Professor Ruth Okediji of Harvard Law School delivered the 41st Foulston Siefkin LLP Lecture to a standing-room-only crowd at Washburn Law. Her presentation “The Right to Own?: Protecting Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge in the Age of Intellectual Property” delved into the complicated and ever-evolving intellectual property (IP) issues surrounding traditional knowledge and genetic resources.

On April 12, Professor Ruth Okediji of Harvard Law School delivered the 41st Foulston Siefkin LLP Lecture to a standing-room-only crowd at Washburn Law. Her presentation “The Right to Own?: Protecting Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge in the Age of Intellectual Property” delved into the complicated and ever-evolving intellectual property (IP) issues surrounding traditional knowledge and genetic resources.

Jordan Z. Dillon, 2017-18 editor-in-chief of the Washburn Law Journal, contextualized the lecture’s topic within the journal’s theme for volume 57: change and reaction to change. “The world around us, and the law, are changing faster and faster every year. If what we have is constantly changing, what does it mean to have something, to own something? We have to challenge our assumptions,” he said.

Okediji described the “complex international framework” across which traditional knowledge is spread, including all areas of conventional IP law: patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets. She focused on the tensions which slow and muddle conclusive policy regulations among various stakeholders, including inventors, policymakers, indigenous peoples, and IP administrators.

“The mismatch we often see is between the intellectual property system and the way in which indigenous groups view questions of ownership, access, and use,” she said. “It’s an international issue in many ways, and it’s been escalating in the past 10 years. The heart of the issue tends to be the interface between what many indigenous folks would refer to as misappropriation of their knowledge; misappropriation of genetic resources, both human and plant; [as well as] misappropriation of traditional knowledge surrounding how that genetic resource might be used.”

Okediji explained that scientists and inventors often learn about traditional resources and practices through observation, then race back to their own countries to patent the knowledge. The issue of unfairness is raised when that individual or entity refuses to share royalties with the originators of the knowledge.

“Many indigenous peoples tend to be the poorest, most politically marginalized, and most ignored communities around the world,” she said, expounding that to not recognize the value, both economic and noneconomic, that indigenous knowledge brings, is to continue to exclude them from their national discourses.

Okediji concluded that various innovations; specifically medical, environmental, and biotechnological; “rest on the shoulders of the most vulnerable global populations,” requiring further consideration of how indigenous peoples’ traditional knowledge can be protected from misuse and misappropriation without slowing advancement of necessary products like medicine.

“Many industries in the United States alone would be impacted by a rule that said indigenous groups are entitled to control the plants and any knowledge they’ve cultivated about those plants over the years,” she said. “But in the absence of property rights, you can still have an obligation to share the results of commercialization with the groups from whom you got that knowledge.”

For more information about the lecture, please see the 2018 lecture page.